Joseph Bell and a Writer’s Trip to Edinburgh

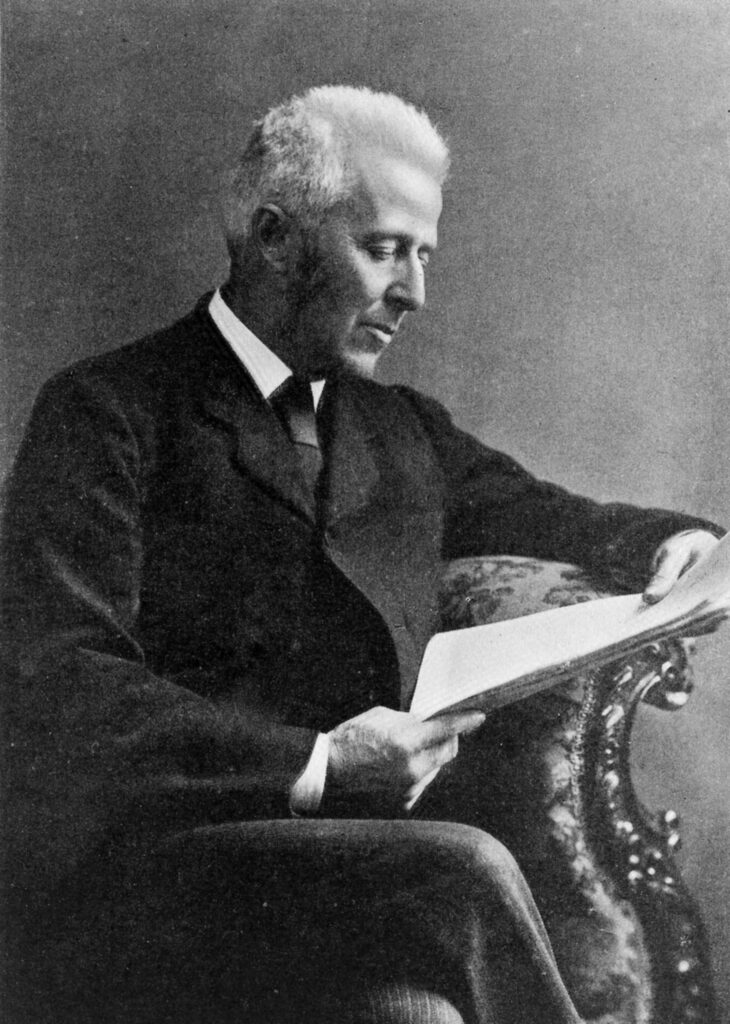

Joseph Bell came up twice in my Holmesian meandering in the last four weeks. When you really try to find out who Sherlock Holmes is, was, or might be, Joseph Bell wants a word. When you find out at Baker Street Museum that many people have written countless letters addressed to the great detective, genuinely believing Sherlock Holmes was a real person, you begin to feel that some research needs to be made pertaining to the real person who did inspire him, if loosely, as Doctor Bell I think would hope me to say.

Much like Conan Doyle had a conflicted relationship with our favourite consulting detective, because his popular short stories were in the way of his ‘serious’ historical fiction, Joseph Bell felt uneasy about the connection between himself and Sherlock Holmes. It was not quite as bad as the pangs Doctor Frankenstein felt towards his creature, but the resentment accompanied Bell for the rest of his life. It is this conflict between Bell’s inspiring personality and the extremely lifelike imitation that is the character of Sherlock Holmes, which drew me to dig deeper into the Scottish surgeon’s singular life.

From Conan Doyle to Google Street View

Of course, my travels for Spiral Mind and its sequels (yes, plural!) led me to Edinburgh. They would have had to, even without Joseph Bell, since Conan Doyle wrote most of the first stories in Edinburgh. I felt very much akin to Conan Doyle in my efforts to depict a roaring London, with nothing but maps to help me. While Doyle famously used paper maps to outline any route taken by the characters in the stories, which earnt him great praise even from Londoners, I was fortunate enough to have Google street view on my side.

Whatever maps you use, though, the process is laborious, and the more I did it, for over a year before I was finally able to visit London for the first time, which you can read about here, I started to wonder why Conan Doyle wasn’t viewing his Sherlock Holmes stories as ‘serious’ fiction, and why he harboured such negative feelings towards his main character. You have to be taking your writing very seriously indeed if you want to navigate yourself through the entirety of London with a character present who apparently knows every side street like the back of his hand. I suppose there are drawbacks to writing about Sherlock Holmes, but I digress.

Joseph Bell’s Edinburgh

Edinburgh presented itself in exactly the gloomy Victorian light I had always imagined it when I exited the train station. The castle loomed large above the city, the blackened walls of tall Victorian buildings loomed even taller, and the grey clouds darkened the shadows in the streets. Sure, Joseph Bell wouldn’t have seen a neon sign of Boots the chemist on a dark and looming storefront, but I have visited my fair share of historical apothecary’s shops to imagine their brown bottles jingling in wooden cabinets, the delicate metal scales and their copper drain pipes. There was something suggestive about the streets of Edinburgh, which explained the many famous literary figures and characters that originated here.

Real Life Inspiration

Since I only had one day in Edinburgh, I quickly made my way to the Surgeons’ Hall, where one small part of an exhibition was dedicated to Joseph Bell, whose influence on forensic science has sadly been overshadowed by his influence on the most portrayed literary human character of all time. Doctor Bell was among the first surgeons to be called upon by the police to investigate forensic evidence – a practice which would soon become standard. For example, he was famously consulted in the case of the Ardlamont murder, where a young boy was shot when out hunting with a man who had recently taken out life insurance on the boy. You can read all about the case in the Surgeons’ Hall blog.

Joseph Bell even ended up investigating the Ripper murders, but his verdict on who Jack the Ripper was was mysteriously lost in the post. It is certainly his distinguished deductive reasoning which Bell gave to Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle was, on multiple occasions, perplexed by Bell’s observations about patients, which not only inspired Sherlock Holmes as a detective, but also Doctor Watson, who stood in for Doyle.

The Haunted Doctor

Conan Doyle widely publicised the real life inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, but sadly, Joseph Bell felt, ‘haunted by my double, Sherlock Holmes.’ Not only did the fictional ‘double’ overshadow him, but Bell was unhappy about how coldly Conan Doyle had portrayed the deductive reasoner in his story. Bell said, ‘I hope folk that know me see another and better side to me than what Doyle saw.’ It is exactly this tension which drew me to Joseph Bell, and it inspired something entirely different in my sequel to Spiral Mind. Joseph Bell should have his say, I thought, and found a way to weave his words into my story.

The question, ‘Is Sherlock Holmes real?’ is still widely asked, and for decades, the Sherlock Holmes Museum in Baker Street had to employ an assistant to answer the mail for all those who were convinced Sherlock Holmes was a real person, even though Conan Doyle had never protested any such thing. It could be said that to a large extent it is Bell’s incredible talent which gives so much life to the great detective and the ongoing belief in him. At the same time, the question, ‘Is Sherlock Holmes a real person?’ cannot be answered with a yes, as Bell would not want to be remembered as the cold, calculating machine Conan Doyle put on the page. Perhaps this is one of the reasons, Sherlock Holmes grows softer in the later stories, written after Bell died in 1911. Conan Doyle might have felt his character, like his inspiration, should be human, after all.